Wisdom in the southeast comes in many forms, even delivered in my native language. As seen parked in front of our vehicle as we left Urfa.

“But we have to take your guests there. These are very important saints. You all need a blessing for your trip. It’s the most famous place in Viransehir. Everyone visits; even from other countries. It’s just down this road a little way, not far….” Abit’s cousin Seyhmus implored in his charmingly raspy voice of a much older man, though he’s barely 30. We exchanged glances as he made our decision and turned the car off the main highway that runs along Turkey’s southern border with Syria.

Perhaps he was right. We’d had some unexpected challenges that morning. Back on the road again, we could use some good travel karma. A short detour to see something a local resident thought was so important couldn’t hurt. Some of my best experiences have been spontaneous diversions down an unknown route. Sacred places of all denominations intrigue me; I’ve gone out of my way to light a few candles. Our guests seemed to agree, though maybe they were just being polite and humoring our animated driver, as I translated what he was saying.

A double triumphal arch marked the road’s entrance. Otherwise, there was not much else around, just occasional road workers raising one lane of the road and repaving it. We were jostling along on the untransformed side, watching the flat waving fields of wheat and lentils spread out around us.

Small talk dwindled as we kept going…10 minutes, 15. Murmured asides about being kidnapped in eastern Turkey, as we saw only a few other vehicles on the road, and no obvious landmarks appeared before us. 20 minutes turned to 30, or so I conjectured in my head. I’d stopped wearing a watch years ago. With an attachment to my laptop and the call to prayer 5 times a day, I didn’t need one. I could see how that made some visitors think I’ve fallen victim to Turkish time.

Patience in the back seat wearing thinner, we passed a large school building, like a child’s drawing of brightly colored paint. A small military police station was opposite, with two soldiers visible, guarding the empty terrain. A few kids playing nearby, but otherwise no evidence of any villages around to supply such a school with enough pupils. Beyond, more open fields, mostly green still this early June, but starting to tinge with gold along the side of the road to match the hills on the horizon.

Another 10 minutes, or maybe time just seemed to lengthen in the heat and dust, conversation stalled and a Kurdish folk singer lamenting his losses on the radio. A flash of black and white as our car’s wheels crunched gravel, scaring a bird out of its nest, its whirring wings like a dervish of light and dark against the stalks of gold wheat.

Finally we turn slightly to the left, as a large grove of old olive trees came into view, along with Eyyüp Nebi, a small village of simple concrete homes. “Okay, we’re here!” Seyhmus said, jerking the car into park.

We filed out, happy to stretch our limbs. A short stroll away down a dusty dirt square – more of a crossroads really, with smaller lanes leading out into the village – we follow Seyhmus into a small paved courtyard covered in trees, a mix of olive, mulberry and hibiscus. I asked Abit, “So, you’ve been here before right?” He just smiled. “You’ll like it. It’s old, they are saints.”

The first tomb was under renovation, workers placing blocks of carved tulips into a low wall, scaffolding still covering part of the small domed structure of cream limestone. A few pilgrims, a family of several generations, the women wearing somber headscarves and bundled twill trench coats, were removing shoes before entering the tomb. It seemed too crowded to try to enter, and the men sitting inside looked none too welcoming, even if we foreign women knew which entrance to use. I felt intrusive, not even taking a photo.

So we wandered around the back to admire the green trees and large garden that spread out well beyond. Seyhmus and Abit beckoned for us to return to the tomb, but we could see inside through the arched windows, to the draped coffin with a green and gold embroidered cloth.

Beyond was another small structure of horizontal black basalt and cream limestone, this one half perforated by black ironwork. Inside an oval patch of mossy red earth held a large cracked boulder. Zen garden, Mesopotamian style?

By then, a group of curious local girls had come down from a shady hillside nearby to giggle and ask questions in basic English. Sisters, gold hair and green eyes, with their younger cousins, black eyed and olive skinned, were delighted two of us foreigners could speak Turkish. The oldest girl was practiced, telling us this saint had lost everything, had he lived through his ordeal – pointing at the sign – right here, on this boulder, for years, abandoned by his family. My Catholic upbringing was stirring up memories of Old Testament stories. I knew that Islam shared the same saints and prophets. Who was this saint again?

Sabır. I’d learned the word meant patience. A crucial word to know early on living in this culture, where very little was in my control; sometimes going along for the ride was often the best way to be. I’d been told too many times sabır ol – be patient. Calm down, let things happen.

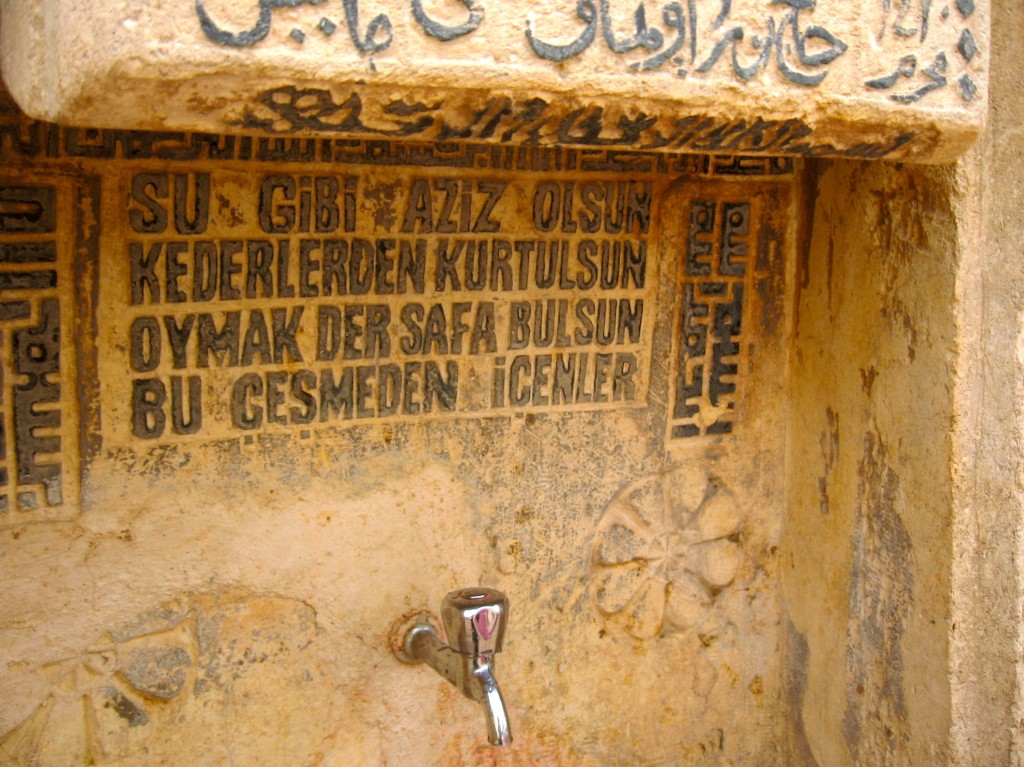

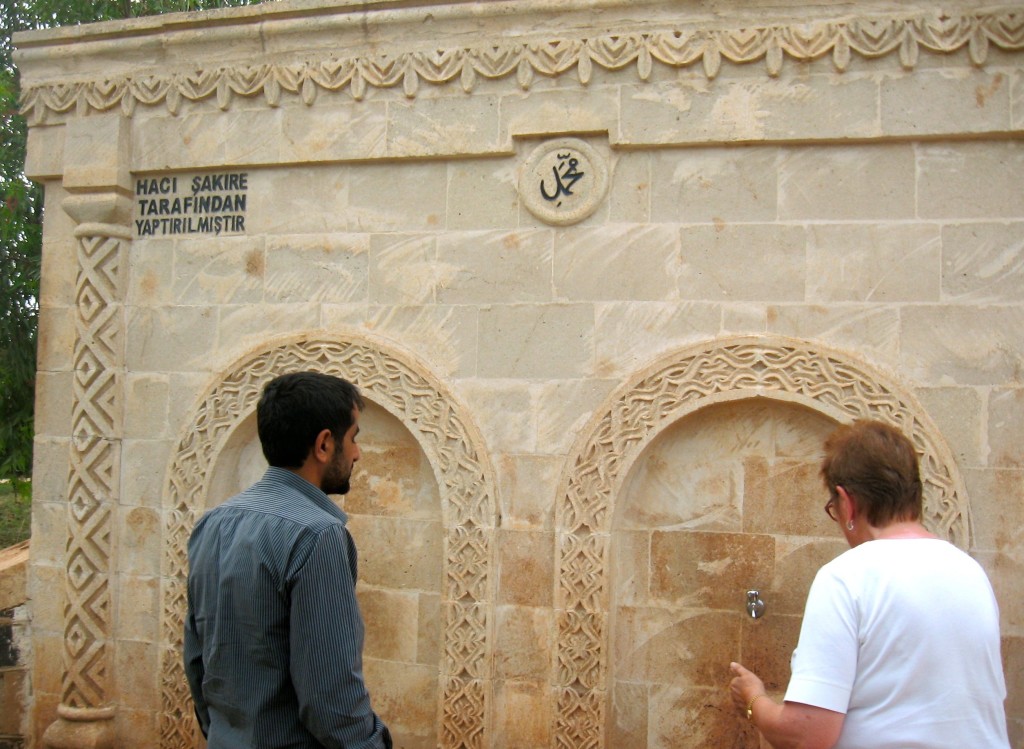

A final monument, this time enclosing a small fountain of “healing water” according to the sign. Though it all looked ancient, the top was only placed in 1999, the year I moved to Turkey. Below there was a verse in modern Turkish I could partly decipher, among the Ottoman, Arabic and Kufic scripts:

Su gibi aziz olsun kederlerden kurtulsun oymak der safa bulsun bu ceşmeden içenler

May the saints save drinkers from this fountain from grief …and something else about “carving that tells of the purity found”.*

A mangled translation, but sometimes it’s enough just to understand the essence, not every literal word. Turkish and English are too different, so opposite in their structure and expression. “Patience is the key to paradise” in this country full of sayings, set phrases and proverbs.

* A far more accurate translation, from a woman brave and talented enough to translate Turkish literature into English:

Good wishes for water,

Oymak bids that all who drink here

Be freed from worries

And find pleasure

We went through the motions of washing our hands and faces, though only Abit and Seyhmus were brave enough to drink the water.

Slowly strolling back to the car, still hot and mystified by the visit, one of our group noticed a sign with the saints’ names, overlooked in our haste to get out of the car.

“OH. Eyyup. That’s Job!!!”

Suddenly the meaning of the fountain and the boulder became clear. Patience to come through an ordeal. Now I understood Sehymus’ desire for our visit, his bafflement why we had not immediately agree after our delayed morning. We were all “people of the Book”; this was our story too, something we had in common. Laughing as we piled back into the car, I hoped to keep the lesson of this day with me the rest of the trip.

Leave a Reply